COVID-19 in the United States Incarcerated Population

Author: Sylvia Y. Sontheimer (MS4, University of Alabama-Birmingham)

Editor: Lauren Walter, MD

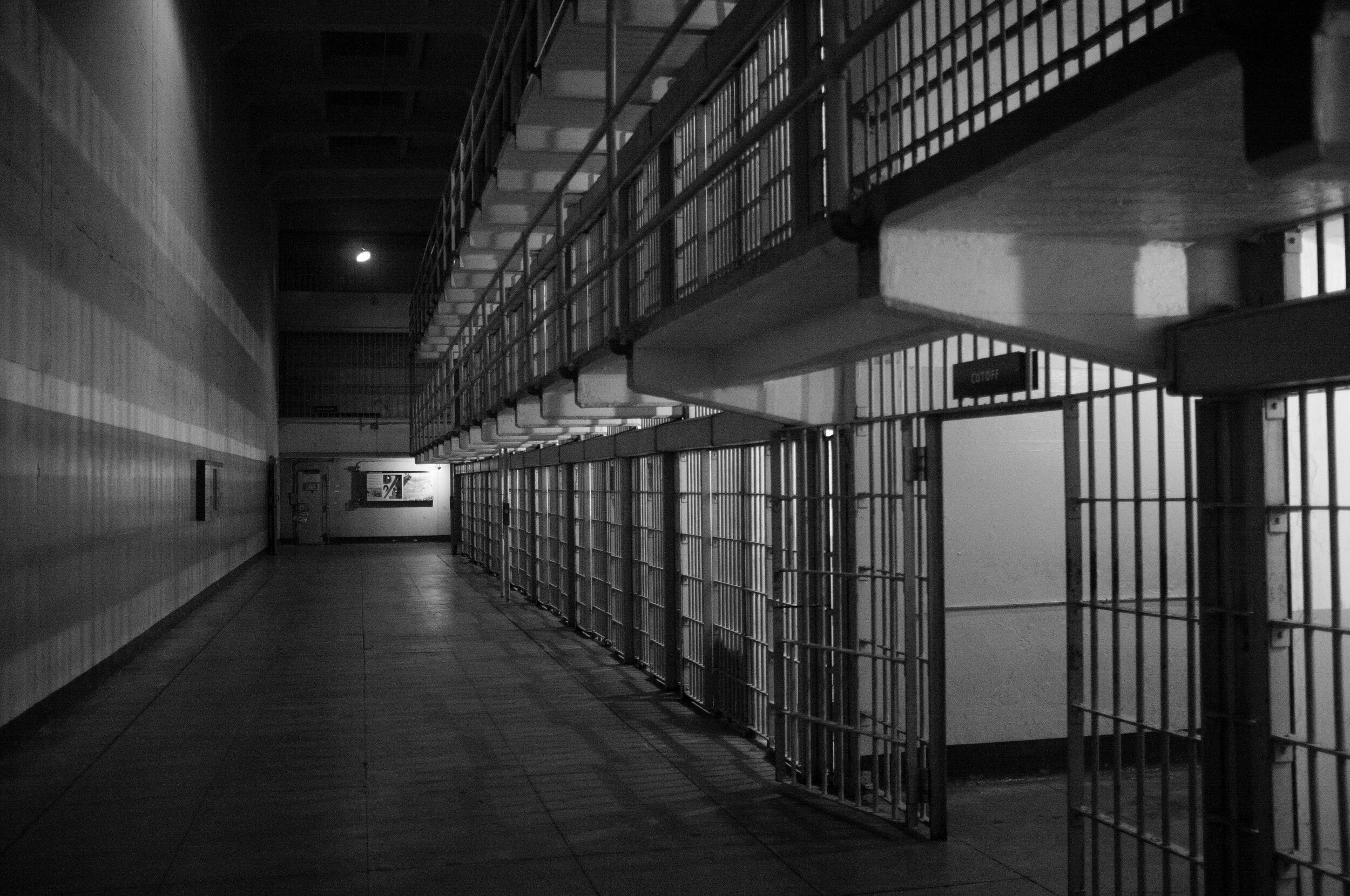

As COVID-19 has ravaged the United States – surpassing 7,000,000 cases and 200,000 deaths as of September 25th (1)—it is clear that vulnerable populations have been hit the hardest. As Dr. Ayesha Khan eloquently writes in her blog piece for Science Speaks, “Infectious outbreaks exacerbate pre-existing social inequities and expose the ugliest systemic injustices” (2). This is especially true for the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on incarcerated individuals in the United States (US). A recent JAMA article revealed the COVID-19 case rate for individuals in federal and state prisons to be 5.5 times higher than the rest of the US population. Further, when adjusted for age and sex, the death rate for this population was found to be three times that of the US population (3). Not only is COVID-19 more prevalent among incarcerated individuals—it is also more deadly.

Methods that have been promoted to prevent disease transmission, such as social distancing practices, are notoriously difficult in prisons, jails, and detention facilities, which are often already overcrowded and do not allow space for isolation (4,5). This, coupled with officers and staff members regularly entering and exiting facilities, lack of personal protective equipment and insufficient testing in these facilities, all contribute to the disparity in case and death rates (5).

A report by The Marshall Project found that many in prisons, jails, and detention facilities were only testing those who were symptomatic, as opposed to testing contacts of positive patients (regardless of if they were symptomatic or not), or testing everyone in the facility (6). Neuse Correctional Institution, a facility in North Carolina that tested all incarcerated individuals and staff, found that 65 percent of people tested positive for COVID-19, with 98 percent of these people being asymptomatic (6). This suggests that the COVID-19 case rate is likely exponentially higher than the numbers reported by Saloner et al., demonstrating an even greater disparity in cases between incarcerated individuals and the general population.

It is imperative to recognize that Black Americans are disproportionately impacted by the disparity in COVID-19 cases and deaths in the incarcerated population. Due to centuries of oppression and systemic racism within the criminal justice system, Black Americans make up 33% of the prison population, while only making up 12% of the US population, whereas non-Hispanic White Americans make up 30% of the prison population, but make up 64% of the US population (7). Federal policies within the War on Drugs movement, such as the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, have largely contributed to these disparities which still persist today (8). Thus, the impact of any external factor, including a pandemic, on our system of mass incarceration has a disproportionate and unjust effect on Black Americans.

Some states have addressed the issue of COVID-19 spread in prisons and jails by implementing decarceration strategies such as eliminating bail or releasing individuals who are held pretrial or who are incarcerated for nonviolent offenses (9). Though critics may argue that such strategies may lead to a surge in crime, a report from the ACLU found that crime rates in nearly every city studied between March and May 2020 were lower than the same months in 2019, and that the rates were unrelated to the change in prison populations during that time period (10).

As aforementioned, incarceration itself is a risk factor for transmission of communicable diseases. Reducing the number of individuals in prisons and jails is a harm-reducing strategy that has the potential to save thousands from exposure to COVID-19, thus eliminating the risk of having long-term consequences related to COVID or dying of the disease. Prevention of cases and eliminating prison “hot-spots” –areas with rapidly increasing COVID case rates in a short amount of time—would also further decrease the burden of disease on the healthcare system, specifically emergency departments, where acutely ill incarcerated individuals are often first evaluated.

However, it is important to recognize that decarceration strategies are only a temporarily solution in response to the current pandemic, and widespread change is necessary within our criminal justice system which disproportionately arrests and incarcerates people of color (11). Both law enforcement violence and mass incarceration have been named as public health crises, and we as health care providers should be advocating for change in these systems as they are both players in health inequities nationwide (12, 13). As Michelle Alexander states in the new Preface of The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, “…we need to hold people accountable in ways that aim to prevent and repair harm rather than simply inflicting more harm and trauma and calling it justice” (8).

Sources:

1. CDC – Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) – CDC COVID Data Tracker. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#cases_casesinlast7days. September 24, 2020.

2. Khan, Ayesha. “Racism, Not Race, Is a Risk Factor for Infectious Diseases.” Science Speaks: Global ID News, 15 Aug. 2020, sciencespeaksblog.org/2020/08/03/racism-not-race-is-a-risk-factor-for-infectious-diseases/.

3. Saloner B, Parish K, Ward JA, DiLaura G, Dolovich S. COVID-19 Cases and Deaths in Federal and State Prisons. JAMA. 2020;324(6):602–603. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.12528

4. McCarthy, Niall. “The World's Most Overcrowded Prison Systems.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 30 Jan. 2018, www.forbes.com/sites/niallmccarthy/2018/01/26/the-worlds-most-overcrowded-prison-systems-infographic/.

5. Hawks L, Woolhandler S, McCormick D. COVID-19 in Prisons and Jails in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(8):1041–1042. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1856

6. Aspinwall, Cary, and Joseph Neff. “These Prisons Are Doing Mass Testing For COVID-19-And Finding Mass Infections.” The Marshall Project, The Marshall Project, 24 Apr. 2020, www.themarshallproject.org/2020/04/24/these-prisons-are-doing-mass-testing-for-covid-19-and-finding-mass-infections.

7. Gramlich, John. “The Gap between the Number of Blacks and Whites in Prison Is Shrinking.” Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center, 27 Aug. 2020, www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/30/shrinking-gap-between-number-of-blacks-and-whites-in-prison/.

8. Alexander M. The new Jim Crow: mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New York, NY: The New Press, 2010.

9. Prison Policy Initiative. “Criminal Justice Responses to the Coronavirus Pandemic.” Criminal Justice Responses to the Coronavirus Pandemic | Prison Policy Initiative, 11 Sept. 2020, www.prisonpolicy.org/virus/virusresponse.html.

10. ACLU Analytics. “Decarceration and Crime During COVID-19.” American Civil Liberties Union, 27 July 2020, www.aclu.org/news/smart-justice/decarceration-and-crime-during-covid-19/.

11. Nowotny, Kathryn, et al. "COVID-19 Exposes need for progressive criminal justice reform." (2020): e1-e2.

12. Brinkley-Rubinstein, Lauren, and David H. Cloud. "Mass incarceration as a social-structural driver of health inequities: A supplement to AJPH." (2020): S14-S15.

13. American Public Health Association. "Addressing law enforcement violence as a public health issue." Policy Statement 201811 (2018).