Emergency Medicine and Reproductive Healthcare in a Post-Roe Landscape

Written by: Kelli L. Jarrell, MD, MPH

Edited by: Katherine Jarrell, PharmD; Alexis Kimmel, MD; Melanie Yates, MD

On June 24, 2022, the Supreme Court passed a 6-3 decision, overturning the historic Roe v. Wade decision. The court held that there is no longer a federal constiutional right to an abortion and that the authority to regulte abortion rests with the people and their elected representatives, placing decisions about the legality of abortion in the hands of the states.1 In the aftermath of this decision, physicians of all specialties are questioning what healthcare will look like in the post-Roe landscape. This is especially in states with trigger laws, laws that were on the books and operative immediately in the future event that the court ever removed the protections of Roe.2

The American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) published this policy statement on June 24, 2022 from their June 2022 board meeting: “The American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) believes that emergency physicians must be able to practice high quality, objective evidence-based medicine without legislative, regulatory, or judicial interference in the physician-patient relationship.”3 The current president of ACEP, Gilliam Schmit, MD, FACEP, stated “Decisions by nonmedical professionals that interfere with the physician-patient relationship are extremely worrisome. Politics should never compromise an emergency physician’s ability to have an honest discussion with a patient about their health or to evaluate all treatment options.” The Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act, or EMTALA, requires emergency physicians to treat or stabilize any patient who comes to the emergency department, regardless of their insurance status or ability to pay. This decision could impact the ability of emergency medical providers to provide appropriate care and/or limit open discussions about relevant treatment options for patients. Dr. Schmitz stated: “Emergency physicians are bound by oath and law to care for anyone, anytime. As we assess the range of implications this legal decision could have on patient care and safety, our commitment to patients is unwavering and our dedication to leading care teams that provide high quality, objective and evidence-based emergency care will not change.”4

A number of other healthcare organizations have issued statements following the 6-3 ruling to overturn Roe v. Wade, including the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC), the American Nurses Association (ANA), the American Medical Association (AMA), the World Health Organization, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG), the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), the American Public Health Association (APHA), the American Psychiatric Association (APA), and the American Society of Health System Pharmacists (ASHP).5,6,7 The United States Department of Health and Human Services called the decision “unconscionable.”6

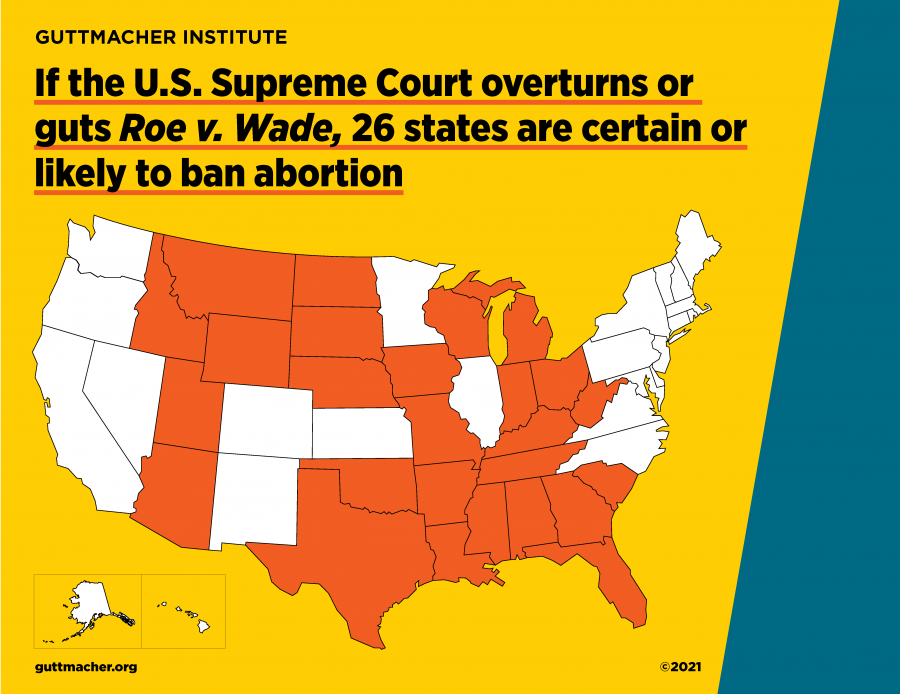

While emergency providers anxiously await the impending changes, it is worth considering the current and historic social landscape of abortion care in the United States. Since 2010, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of laws restricting access to abortion care (Figure 1).8 Twenty-six states are certain or likely to ban abortion following the court’s decision. Although many of the laws are more recent, the law that will go into effect in Wisconsin, unless there is intervention from the state government, dates from 1849. The law in Michigan is also over one hundred years old.9 The majority of these states are in the Southeast, where over half of the country’s Black population lives as well as a significant portion of the country’s Black-Hispanic population, and the Midwest, including the Great Plains, where a majority of the country’s Indigenous population lives. Access to abortion is already severely limited in these areas after the adoption of the Hyde amendment, which limited federal funding for abortion. This is particularly true for Indigenous persons, as the Indian Health Services are entirely federally funded.10 Kellie Copeland, director of Pro Choice Ohio, said of making abortion illegal in the state of Ohio: “If they succeed, it will have a disproportionately harmful impact on Black, Indigenous, and other people of color, the young, people with disabilities, LGBTQ and non-binary people, as well as those living in Appalachia and other rural communities.”11 The United States has the highest maternal mortality rate of ten high-income countries. The mortality rate for non-Hispanic Black women is more than twice that of their non-Hispanic White counterparts. In Mississippi, where the Dobbs case that led to this decision originates, the state ranks last in the country on a composite score of measures including infant mortality, preventable deaths, and children without age-appropriate medical visits in the past year.10 In Mississippi, 74% of the women who received an abortion in 2019 were Black, yet Black women make up just 42% of the child-bearing population. In Idaho, Hispanic women made up 25% of those getting abortions and 15% of women and girls of reproductive age.12 Nearly 60% of the women in these states receiving abortions are in their 20s and 9% are in their teens.10

Figure 1.13

Multiple studies predict an increase in deaths in a post-Roe America. A 2021 study predicts a 21% increase in the number of pregnancy-related deaths with a 33% increase in pregnancy-related deaths for Black women.14 In a 2019 study of pregnant trans and nonbinary people, 19% of respondents reported trying to end a pregnancy themselves with an unsafe method.15 Pregnant people with disabilities have a much higher risk for pregnancy-related complications and death, including eleven times the risk of maternal death.16,17 The passing of Senate Bill 8 in Texas has already showed multiple women seeking abortion care out of state, facing long wait times and economic hardships. Others predict that women unable to surmount these obstacles may try risky or ineffective methods or travel to Mexico where prescriptions can be purchased over the counter. To be clear: safe and effective options for self-administered abortion medications exist in concert with appropriate oversight and access to healthcare providers. However, it remains to be seen if, how, and when this will be implemented and/or how states will attempt to regulate these medications. Medical professionals are trying to interpret complex legislation, made by persons without healthcare training or backgrounds, that impacts the services they provide. This can lead to severe consequences for their patients. Although the charges were later dropped, Lizelle Herrera, a Texan seeking post-abortion care, was charged with murder last month when medical professionals at a Texas hospital likely reported her to law enforcement, despite the fact that Texas law specifically prohibits criminal charges for women aborting their pregnancies.18

The Turnaway study recruited women from 30 abortion facilities from 2008 to 2010 and conducted thousands of interviews, both of women who received an abortion and the “turnaways” or those who were denied an abortion because they were beyond the gestational limit in that state.19 This study found that denying a woman a wanted abortion has lasting financial, emotional, and physical effects for mothers as well as worse outcomes for existing children in these mothers families. Being denied a wanted abortion correlated with an increase in household poverty lasting four years longer than counterparts who received an abortion. Being denied an abortion lowered a woman’s credit score, increased a woman’s amount of debt and increased the number of their negative public financial records, such as bankruptcies and evictions. Physical violence from the man involved in the pregnancy decreased for those who received an abortion. The children of women denied an abortion showed worse child development compared to the children of women who receive one; children born as a result of an abortion denial were more likely to live below the federal povetry level; and carrying an unwanted pregnancy is associated with poorer maternal bonding. Women who were denied an abortion and gave birth reported more life-threatening complications like eclampsia and postpartum hemorrhage compared to those who received wanted abortions. Two women died during complications associated with delivery after being denied an abortion; no one died as a result of receiving an abortion.19,20

One of the most consequential laws affecting the practice of emergency medicine in the post-Roe era is the Emergency Medicine Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA). EMTALA is a federal law and therefore supersedes state laws, including existing and future state abortion laws. Its definition of a medical emergency therefore trumps life-or-health exceptions in any state abortion ban. Typically, these exceptions in state abortion laws are narrow.21 EMTALA’s definition of a medical emergency is broader and includes any person in labor or suffering from a condition that, without immediate attention, could be reasonably expected to seriously jeopardize their health, impair a bodily function, or cause dysfunction in an organ.22 This definition covers many urgent pregnancy conditions, including PPROM, ectopic pregnancy, and complications from incomplete miscarriage or self-managed abortion.21,23 Furthermore, state law is not a justification for transfer under EMTALA; only patient preference and medical risk-benefit. Because EMTALA has broader protections for patients and supersedes state law, it can be used to protect patients and their health even in states with extremely restrictive abortion laws.21 This has implications for emergency providers and their role in the post-Roe landscape, especially in the coming weeks as states decide what restrictions to place on abortion care in their states.

33.6 million of the United States’ 64 million reproductive-age women live in states at risk of losing access to abortion. Depending on the coming weeks, there may not be a single abortion provider along the Gulf Coast. Women from the Deep South may have to travel as far as Illinois for the nearest abortion clinics.12 One study showed that from 2009-2013, only 0.01% of all emergency department visits for women aged 15 to 49 years old were abortion-related. Of these, 20% were classified as a major incident, defined as requiring blood transfusion, surgery, or overnight inpatient admission. Of these, 1.4% of these visits were due to possible self-attempts at abortion.24 This number is likely to increase. It is nearly impossible to extrapolate pre-Roe data to our post-Roe healthcare climate. This is especially true for emergency medicine. ACEP was founded in 1968 and emergency medicine was recognized as a speciality by the AMA in 1972, just one year before Roe. The first residency training program was founded in 1970 and the American Board of Emergency Medicine was not founded until 1976, three years after Roe was codified.25 EMTALA was passed in 1986. The specialty has changed tremendously since the pre-Roe landscape and will likely have little guidance to draw on from this period. While it remains to be seen how EMTALA will interact with new laws passed in the coming months, it is certain that emergency providers will face some of these upcoming challenges at night, when our legal departments are fast asleep. At times when decisions have to be made to preserve the health, safety, and well-being of patients.

References:

United States Supreme Court. 19-392 Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. 24 June 2022. Accessed 26 June 2022, <https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/21pdf/19-1392_6j37.pdf>.

Jimenez, J. What is a trigger law? And which states have them? The New York Times. 4 May 2022. Accessed 26 June 2022, <https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/04/us/abortion-trigger-laws.html>.

American College of Emergency Physicians. Statement: Interference in the Physician-Patient Relationship. 24 June 2022. Accessed 26 June 2022, <https://www.acep.org/home-page-redirects/latest-news/statement-interference-in-the-physician-patient-relationship/>.

American College of Emergency Physicians. Emergency Physicians Deeply Concerned by Laws that Interfere with the Physician-Patient Relationship. 24 June 2022. Accessed 26 June 2022, <https://www.acep.org/home-page-redirects/latest-news/emergency-physicians-deeply-concerned-by-laws-that-interfere-with-the-physician-patient-relationship/>.

Carbajal, E. and Gleeson, C. 13 Healthcare responses to Roe v. Wade reversal. Becker’s Hospital Review. 24 June 2022. Accessed 26 June 2022, <https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/public-health/12-healthcare-responses-to-roe-v-wade-reversal.html>.

Cochran, A. Medical organizations react to Supreme Court decision to overturn Roe v. Wade. Click2Houston.com. 24 June 2022. Accessed 26 June 2022, <https://www.click2houston.com/features/2022/06/24/medical-organizations-react-to-supreme-court-decision-to-overturn-roe-v-wade/>.

American Society of Hospital Pharmacists. ASHP Calls for Patients’ Right to Access Reproductive Health Services. 28 June 2022. Accessed 26 June 2022, <https://www.ashp.org/news/2022/06/28/ashp-calls-for-patients-rights-to-access-reproductive-health-services>.

Nash, E, Benson Gold, R, Rathbun, G, and Ansari-Thomas, Z. Laws Affecting Reproductive Health and Rights: 2015 State Policy Review. Accessed 24 June 2022, <https://www.guttmacher.org/laws-affecting-reproductive-health-and-rights-2015-state-policy-review>.

Heim, Madeline. If Roe is overturned, Wisconsin law would allow abortion only to ‘save the life of the mother.’ Doctors say it’s not always so clear-cut. Post Crescent. 15 May 2022. Accessed 26 June 2022, <https://www.postcrescent.com/story/news/2022/05/10/doctors-say-wisconsin-abortion-laws-lifesaving-exception-vague-if-roe-v-wade-overturned/7402200001/>.

Bain, M, Bouchard-Gordon, N, and Ruble, A. Restricting Abortion Rights Will Hurt the Most Vulnerable Populations. Johns Hopkins Alliance for a Healthier World. 6 May 2022. Accessed 26 June 2022, <https://www.ahealthierworld.jhu.edu/ahw-updates/2022/5/5/abortion-equity>.

The Columbus Dispatch. Supreme Court Decision: Ohio officials react as Roe v. Wade overturned. The Columbus Dispatch. 24 June 2022. Accessed 26 June 2022, <https://www.dispatch.com/story/news/politics/2022/06/24/scotus-roe-v-wade-reactions-officials-ohio-abortion-law/7722909001/>.

Cai, W, Johnston, T, McCann, A, and Schoenfeld Walk, A. Half of U.S. Women Risk Losing Abortion Access Without Roe. The New York Times. 7 May 2022. Accessed 26 June 2022, <https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/05/07/us/abortion-access-roe-v-wade.html>.

Guttmacher Institute. If the U.S. Supreme Court overturns or guts Roe v. Wade, 26 States are certain or lertain to ban abortion. 2021. Accessed 26 June 2022, <https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/images/scotus_landing_page_map_26_states.png>.

Stevenson, AJ. The Pregnancy-Related Mortality Impact of a Total Abortion Ban in the United States: A Research Note on Increased Deaths Due to Remaining Pregnant. Demography 1 December 2021; 58 (6): 2019–2028. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/00703370-9585908.

Moseson H, Fix L, Gerdts C, et alAbortion attempts without clinical supervision among transgender, nonbinary and gender-expansive people in the United StatesBMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health 2022;48:e22-e30.

National Institute of Health. NIH study suggests women with disabilities have higher risk of birth complications and death. NIH News Releases. 15 December 2021. Accessed 24 June 2022, <https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-study-suggests-women-disabilities-have-higher-risk-birth-complications-death>.

Gleason, JL, et al. Risk of adverse maternal outcomes in pregnant women with disabilities. JAMA Network Open. 2021.

Kitchener, C, Reinhard, B, and Crites, A. A call, a text, and apology: How an abortion arrest shook up a Texas town. The Washington Post. 13 April 2022. Accessed 24 June 2022, <https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2022/04/13/texas-abortion-arrest/>.

University of California San Francisco. The Turnaway Study. Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health. 2022. Accessed 24 June 2022, <https://www.ansirh.org/research/ongoing/turnaway-study>.

University of California San Francisco: Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health. The Harms of Denying a Woman a Wanted Abortion: Findings from the Turnaway Study. 16 April 2020. Accessed 24 June 2022, <https://www.ansirh.org/sites/default/files/publications/files/the_harms_of_denying_a_woman_a_wanted_abortion_4-16-2020.pdf>.

Donley, G, and Chernoby, K. How to Save Women’s Lives After Roe. The Atlantic. 13 June 2022. Accessed 24 June 2022, <https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/06/roe-v-wade-overturn-medically-necessary-abortion/661255/>.

Social Security Administration. Examination and Treatment for Emergency Medical Condition and Women in Labor. Compilation of the Social Security Laws. Accessed 26 June 2022, <https://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title18/1867.htm#>.

Donley, G, Rebouché, R, and Cohen, DS. Existing Federal Laws Could Protect Abortion Rights Even if Roe is Overturned. 24 June 2022. Accessed 26 June 2022, https://time.com/6141517/abortion-federal-law-preemption-roe-v-wade/>.

Upadhyay, U.D., Johns, N.E., Barron, R. et al. Abortion-related emergency department visits in the United States: An analysis of a national emergency department sample. BMC Med 16, 88 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1072-0.

Suter RE. Emergency medicine in the United States: a systemic review. World J Emerg Med. 2012;3(1):5-10. doi:10.5847/wjem.j.issn.1920-8642.2012.01.001.

Resources:

The Supreme Court Decision: https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/21pdf/19-1392_6j37.pdf

Planned Parenthood: https://www.plannedparenthood.org/

National Network of Abortion Funds: https://abortionfunds.org/

Guttmacher Institute: https://www.guttmacher.org/

Aid Access: https://aidaccess.org/en/

For providers who have moral, philosophical, religious, or personal objections to aspects of reproductive healthcare, please consider reviewing this Committee Opinion from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologist Committee on Ethics regarding conscientious refusal in reproductive medicine. It is important for providers from all faith backgrounds to work together in this changing landscape to protect our patients’ safety, health, and wellbeing.